|

| What's So Great about Christianity |

A

thread of secular-themed perspectives has flared up in the public arena to

short-circuit Christianity’s claim to relevance in modern society.

Sceptical

authorities, across the disciplines, are approaching Christianity from a

combative angle, to diminish the faith into a residue of primitive

dispensations.

Secularist

notables such as Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sigmund Freud, Karl

Marx, Fredrick Nietzsche and Charles Darwin, have emerged as the poster-boys of

the “post-Christian enlightenment.”

The

gangly coalition has diffused incredulity to a point where secularist outlook

is the new mainstream among laboratories of culture, while Christianity is fast

becoming a preserve of extremists and isolates.

However,

besides its sustained mojo outside cultural elites, Christianity boasts a rich intellectual

tradition which merits closer recognition in the creative arts, criticism and

apologetics.

Some

of the most enduring influences in the annals of literature, John Milton, Samuel

Johnson, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, T.S Eliot, G.K Chesterton and C.S

Lewis, wrote overtly to “justify the ways of God men.”

In

the realm of apologetics, Lee Strobel, Carl Wieland, Ray Comfort, Alister and

Joanna McGrath and others have demonstrated that Christianity is far from the

intellectually bankrupt syllabus of errors that it has been branded to be.

Had

great minds such as Joseph Addison, Blaise Pascal and Isaac Newton lived today,

they might have been labelled the black sheep of science and philosophy, owing

to the near consensus that the God hypothesis is anathema from academia.

The

few apologists still holding their own are lone criers, out of pitch with the

symphony of their time, but it would be grossly prejudicial to muzzle them on a

“truth by numbers” mob justice clause.

D’Souza’s

apologetics toolkit “What’s So Great about Christianity” is an example of the

growing inventory of articulate and forceful refutations of the “God is dead”

hypothesis.

“What’s

So Great about Christianity” is an unsparing examination of the arguments and rhetoric

underlying the secularist ferment.

The

achievement of the book is its commitment to open inquiry. Open inquiry not

only promises rich academic pickings but acknowledges that both believers and

non-believers may be on different levels of the same ontological ladder as

honest truth-seekers, hence deserve equal attention.

So

instead of tapping into indoctrinatory mode and riding roughshod over alternate

schools of thought with more dogma than reason, D’Souza engages atheists on

their own terms (but does not allow them to leave to leave the boxing ring with

nosebleed).

The

book short-circuits such simplistic and overstretched assumptions as

“Christianity is obsolete,” “an intelligent person cannot believe the Bible”

and “Christianity has been disproven by the Bible.”

However,

De’Souza’s problem statement paints a bleak picture of Christianity’s

functionality in the contemporary laboratories of culture.

“No

longer does Christianity form the moral basis of society. Many of us now reside

in secular communities, where arguments drawn from the Bible or Christian

revelation carry no weight, and where we hear a different language spoken in

church,” D’Souza observes.

“Instead

of engaging this secular world, most Christians have taken the easy way out.

They have retreated into a Christian subculture where they engage Christian

concerns.

“Then

they step back into the secular society where their Christianity is kept out of

sight until the next church service,” he says.

D’Souza’s

prefatory alarm faults today’s Christians for being one more bunch of post-modernists

who live a gospel of two truths; the religious truth reserved for Sunday and

the secular truth which applies the rest of the week.

The

problem with such a comfort zone is that it belies the self-sustaining convictions

and institutes of Christianity and shirks the responsibility to “contend

earnestly for the faith.”

Christians

have embraced with relief Gould’s peace brokerage, the supposition of “Non-overlapping

magisteria” (NOMA), which divides the public arena between reason and faith.

NOMA

rules that the secular society relies on reason and decides matters of fact while

the religious community relies on faith and decides on matters of values.

Christians’

acceptance of the pact and a generally pacifist disposition in the realm of

debate has not spared the faith a series of polemics from atheists and

agnostics unapologetically bent to antagonism.

“The

God Delusion,” “End of Faith” and “God is Not So Great” are among the

aggressive anti-faith polemics which seek to dismiss Christianity at all costs.

The

best way to get around the hostility is not retreating deeper into oblivion and

ceding free ammunition to sceptics. Nay, man to man, fire for fire, argument

against argument.

There

is no room for ambiguity and pacifism (in the realm of debate not warfare, lest

I play into the hands of gleeful literalists) in Christian thought.

Christianity

is by its very nature a clarion call to controversy. The Great Commission is a

mandate of universal evangelism (based on specific not ambivalent claims) which

does not come with a guarantee of safe sail but anticipates hostility, reproach

and tribulation.

|

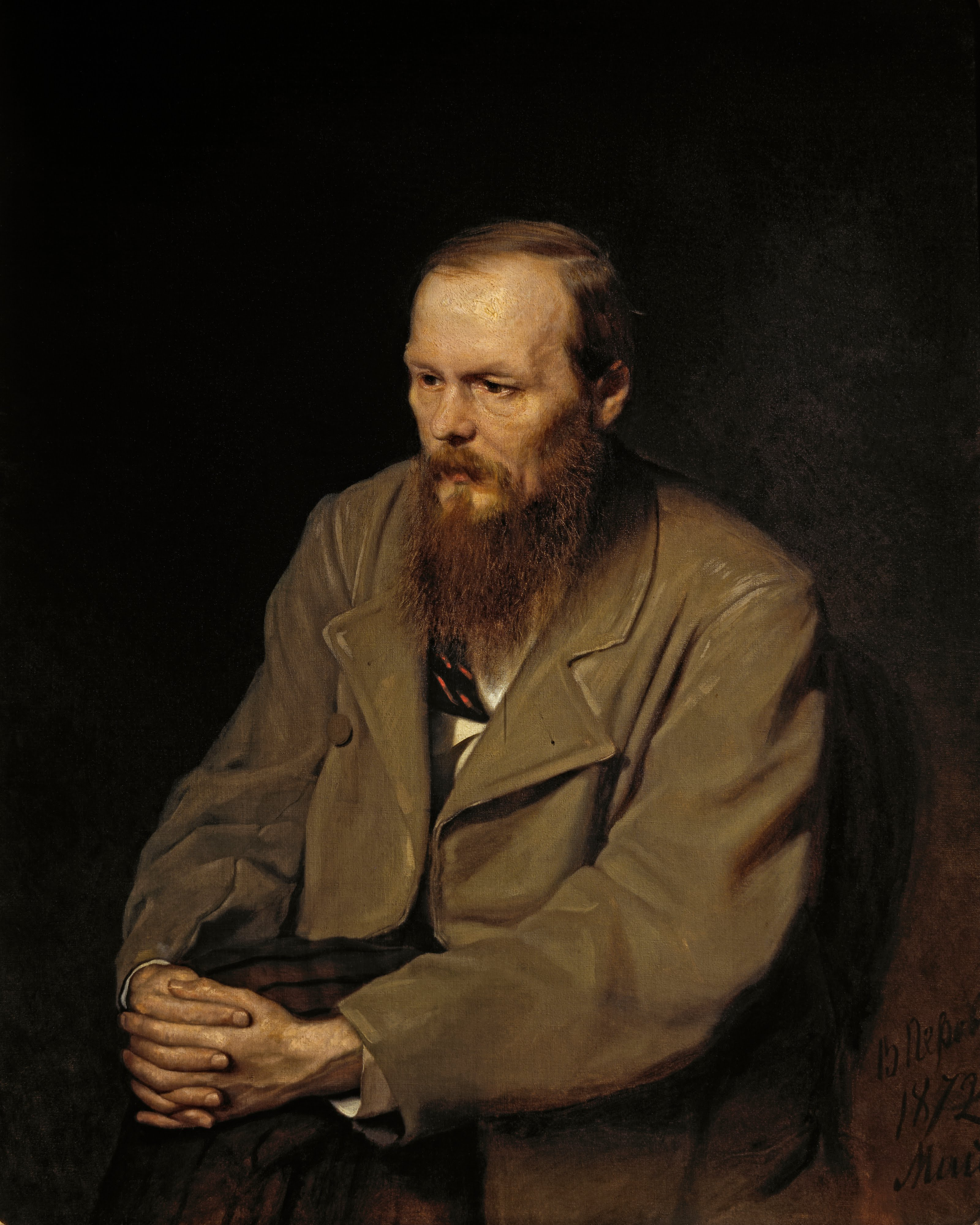

| Dostoyevsky |

“If

every effect in nature has cause, what is the cause of nature itself? Is it

even remotely reasonable to suggest that nature created itself? If for a single

instant there was nothing in existence – no matter, no universe, no God – then

how could there be anything at all?” queries D’Souza.

It

rationally follows that the world was made and someone made it even though, on

the level of empirical enquiry, we may not be able to determine what kind of

creator made the universe. That creator and intelligent first cause

Christianity calls God.

“Our

world looks so physical, yet we can know with scientific certainty that it was

the result of a force beyond physics…Science has discovered a reality which it

had previously consigned to the domain of faith,” D’Souza says.

Observes

Gerald Schroeder: “Theology presents a fixed view of the universe. Science,

through its progressively improved understanding of the world has come to agree

with theology.”

D’Souza

attributes the “survival of the sacred” to the fact that some of the most

important ideas and institutions of modern life emanate from Christianity

Atheism

is more of a death-knell than a stimulus to such key values such as relief and

elevation for the suffering and the preservation of the family institution.

D’Souza’s

book is, however, needlessly flawed by his erroneous classification of

Christianity as a Western religion.

Western

Christendom has, through subservience into an instrument of political

expediency, done more harm than good to Christianity.

Complicity

with, participation in and perpetration of unforgivable atrocities such as the

Inquisition, crusades, slavery and colonialism shows that the Westernisation of

Christianity did more to manipulate, pervert, contradict and undermine than to

advance the faith.

Christianity

has a universal import which cannot be compartmentalised into narrow

demographics as to do so forfeits Paul’s rainbow manifesto that “There is

neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female,

for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

There

still remains to answer atheists’ charge about Christianity being a menace to civil

peace – a charge buttressed by the foregoing atrocities.

Thankfully,

Dostoyevsky wades in just on time. His novel “The Brothers Karamazov,” tells a

story of the grand iniquistor, in which Christ himself appears before the

tribunal, only to be recognised, thrown into prison and told to “go and never

return again.”

“The

reason is clear. Christ’s teachings are those of a peacemaker. They are the

very opposite of the persecutions and violence that has sometimes been

perpetrated in the name of Christianity,” D’Souza says.

No comments:

Post a Comment